Setting Yourself Up for Failure

Part 1: My Epic Fails

I’ve had a lot of opportunities for failure and for success in my career and over the next three posts, I want to share with you how failure is actually a really good thing. And to give you some ways to fail better.

For me, the word “failure” has never really been a part of my vocabulary. It’s not part of my self-talk and I recall very few times where it ever was. Growing up, my parents gave me just enough space to make my own mistakes. From the beginning, I was encouraged early to experiment, to try new things, and to learn from my failures.

I started with fashion. Clearly, I was not meant to be a fashion designer or a fashion model, but I like to think I’ve learned a thing or two from these fashion choices. Do you really want me to show up at work with underwear on my head?

The dictionary definition of failure is "lack of success. And by that definition, it makes it look really scary. And it can be.

I have not failed. I've just found 10,000 ways that won't work. — Thomas Edison

Failure is really learning on our journey toward success. Toward innovation.

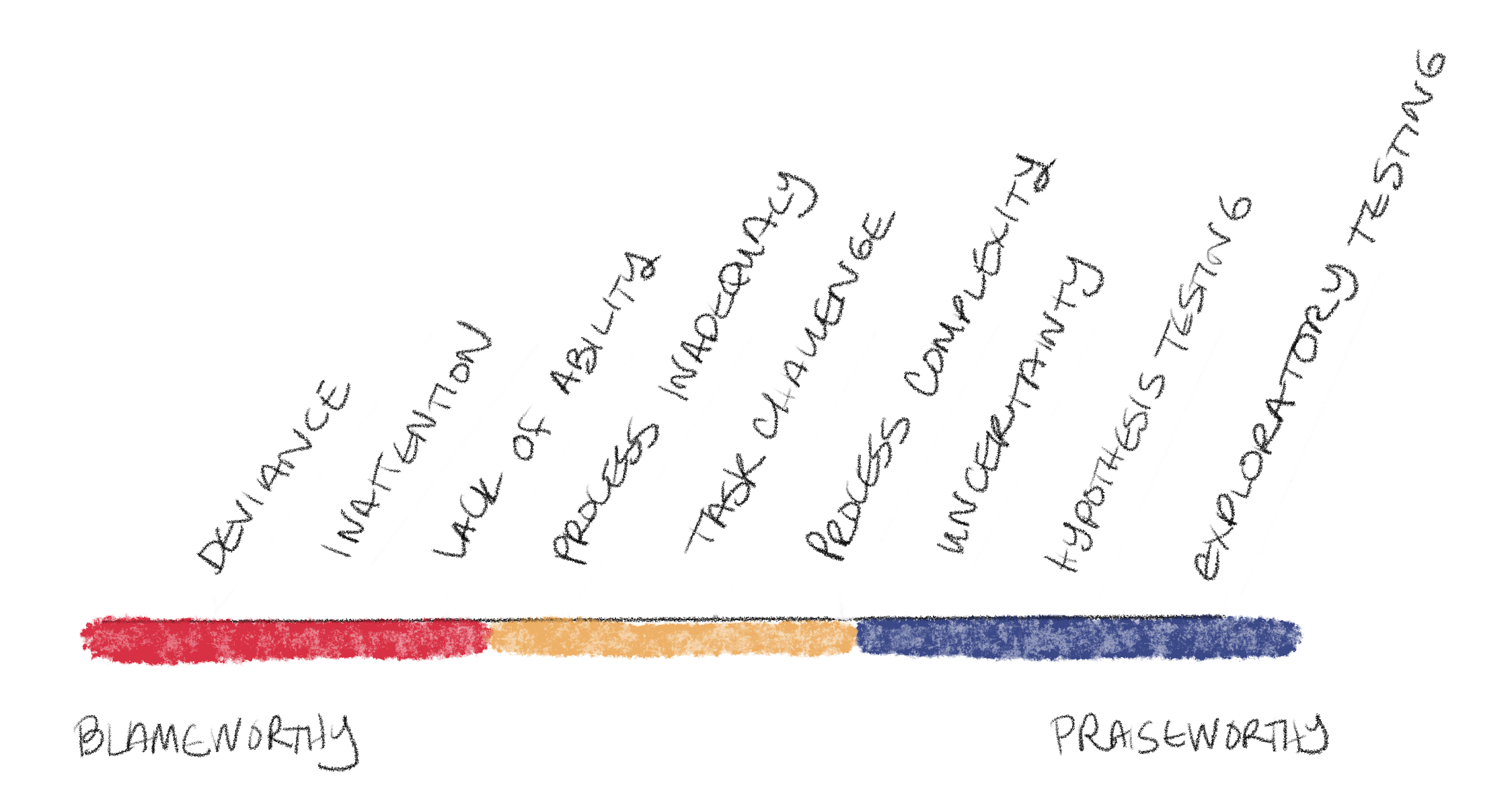

Amy Edmondson is a Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, and has written a handful of books on this topic and she explains that failure is actually a spectrum. Not all failures are good. Not all failures are bad. Some failures are intentional, like someone deciding not to follow a process. Some are because of a lack of knowledge or skill. Some failures are because of complexity or uncertainty. Some are due to experimentation or trying to prove out a new idea.

My epic fails

My first business was a lemonade stand. Every morning in the summer, I would make fresh, cold lemonade. I'd drag out my table and my signs to the street and try to sell lemonade to my neighbors.

But I lived at the end of a dead-end and no one showed up. My second iteration of that business failed in the same exact way. I tried to sell lemonade at my cabin, which was also at the end of a dead-end. My lemonade stands were a dead-end business, but I learned from it. I learned that location matters.

I didn't give up and iterated on my business ideas for a few more years and figured out what my customers really wanted. My next business was a tie-dye t-shirt business.

I had moved my location to a nearby intersection and I'd even set up a booth at a couple of craft fairs nearby. I had more visibility and even a couple of sales. I learned that even though I had made those changes, no one really wanted my one-of-a-kind tie-dye, not even in the late 80s.

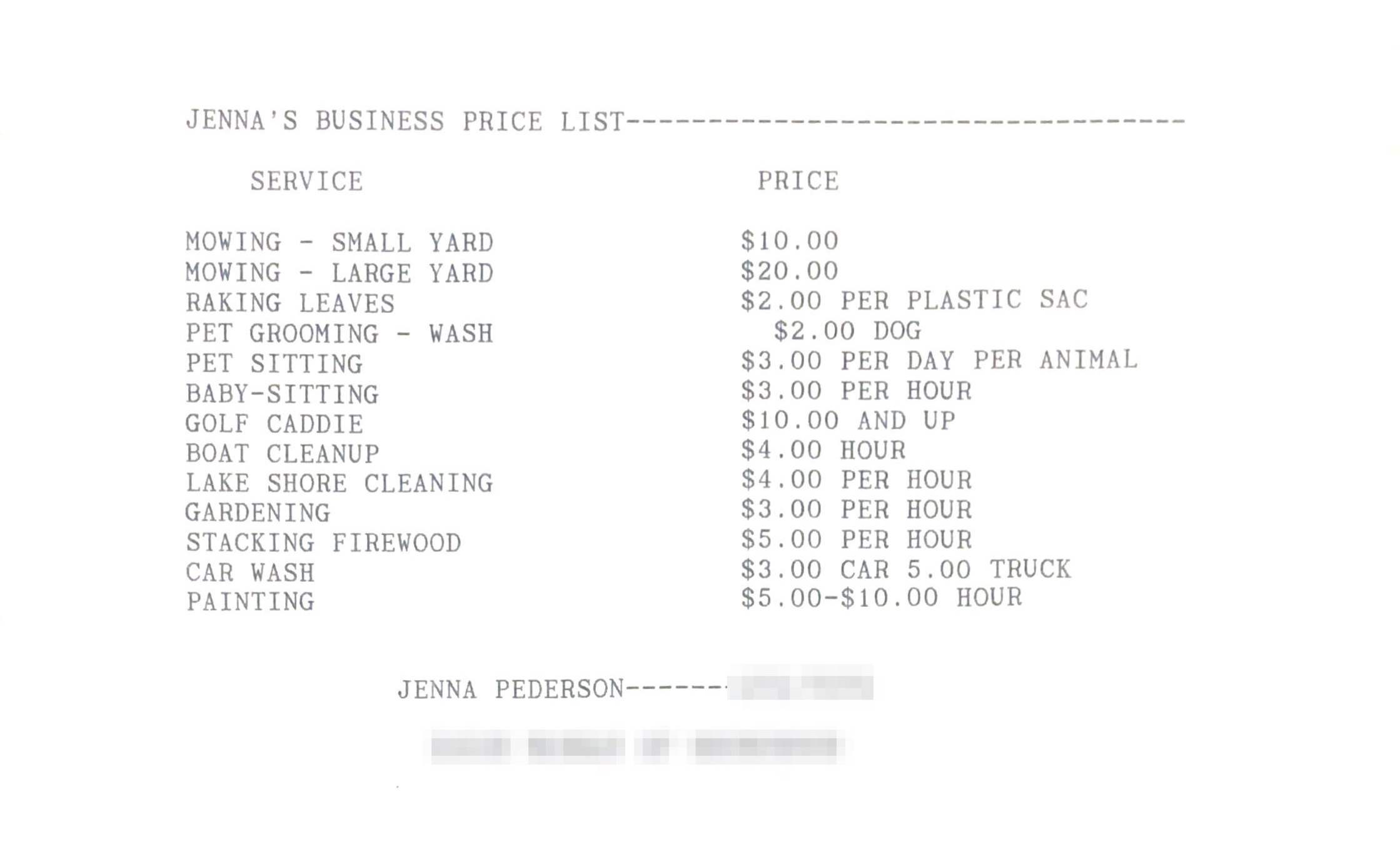

I moved on to an odd-jobs business next.

Lawn mowing was where the money was at! I distributed my pricing sheet to the neighbors and had my first customer. But 20 minutes into my first lawn mowing gig, the muffler fell off the mower, and then I ran over it. Hearing the terrible sound it made, I knew I was done. I just wasn't cut out for lawn mowing.

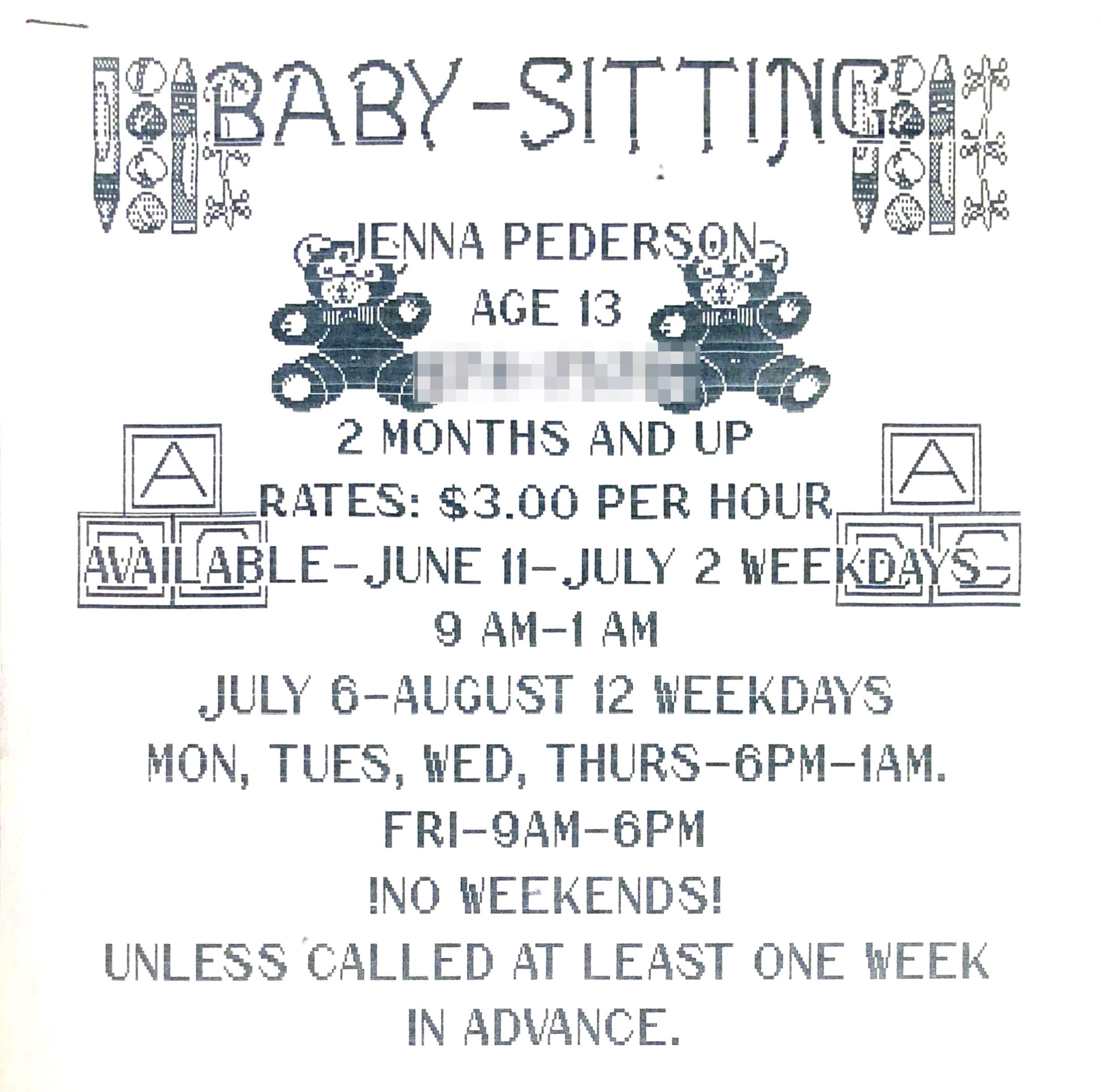

Then after reading all of the Baby Sitter's Club books, I started my own babysitting business.

I distributed these flyers across the neighborhood and I had success! People actually needed my help and they referred me to their friends.

Even though I was just a kid during all of this, I was able to try out these and a few other different ventures and see what stuck. I was given the freedom to fail. I found a lot of things that didn't work (for me or for my customers) and eventually found something that did.

Fast forward a handful of years and a college degree later to my second job out of college. I was a software engineer at an e-commerce company with an online store hosted in 7 different data centers around the world. With upwards of 30 app servers in each one, serving high-levels of traffic to some big-name companies.

One day I was tasked with fixing a bug, one that required a SQL statement to update a record which would force one of the app servers in one data center to pick up the change and run a job. I reviewed the SQL statement a few times, tested it out in our dev environment, sent it off to my manager to run in production, and went back to working on my other tasks.

An hour or so later, my manager called me into his office and we had a really FUN chat. It turns out if you miss part of the WHERE clause and update all the records for that datacenter, then all the app servers in that data center will pick up that change AND kick off that job.

So all of the app servers in that datacenter choked on what was supposed to be one tiny change. With a single SQL statement, I took down one of our 7 datacenters on a Tuesday afternoon.

Thankfully, the datacenter marked itself offline and traffic was rerouted to the other 6 while everything caught up. My conversation with my boss that day could have gone a few different ways. I could have been fired on the spot. I could have been blamed for my mistake in front of my peers, not as a learning opportunity, but as humiliation. Or I could have been congratulated for my mistake.

That day, it was somewhere in between a learning opportunity and being congratulated. I definitely "joined the club" that day though. And I learned a ton, not just more about how our environment was set up and all integrated together. And not just about how I probably should have had another developer closer to the problem review it, rather than my manager. But my biggest takeaway from that experience was that I was working in an environment where not only the people I worked with allowed me to fail (and didn’t fire me for the mistake) but that the architecture of our systems was robust enough to handle my mistake and recover quickly.

I take this story with me everywhere. When someone asks what one of my most memorable failures or mistakes is, this is usually the one that comes to mind, and not just because it was bad, but because I’ve learned so much from it. I've shared it in job interviews, at meetups, and in conference talks.

I always want to be in a position where I’m allowed to fail — where the people around me are ok with it, where we learn from it, whether it’s learning what not to do, what to do better the next time, or learning from a customer on what they actually need vs. what we thought they needed.

But sometimes you're in situations where there's very little room for failure. In fact, failure can literally mean life or death. But you still need to find ways to fail your way toward innovation.

A few years later, I took on a contract with a multinational conglomerate that innovates in many areas including mass transportation. The software we were building was to route trains. We were dealing with infrastructure that was over 100 years old. Not server infrastructure, but physical railway infrastructure. And we were trying to rewrite software written in the 60s in PASCAL.

The people who originally wrote it weren't around anymore. I don't know about you, but I didn't get to learn Pascal in school. What do you do in that situation?

You can implement processes to encourage innovative thinking and put guard rails in place to mitigate risks. We whiteboarded a lot of our ideas. Some of our early processes were mandatory pair programming, rotating pairs every day. This meant that all four of us had our eyes on all the code. We all knew what was going on and we all knew why we made certain decisions. We were all involved in those decisions. Everything we built was also done test-first and we had continuous integration set up to tell immediately when we had breaking changes. We used spikes for exploring solutions quickly and independently of everything else. Because of the nature of this work, our approaches were different than any other project I've been on, which means yours might not look the same.

I wanted to be in a space where I'm allowed to fail so much so that in 2015 Kristen Womack and I decided we needed to create that space for other women.

We wanted to help women get over their fear of starting something whether that be a business or a tech career. We wanted a space specifically for women to feel safe while trying something new, while failing, and learning.

The entire time we were planning our first Hack the Gap hackathon, we were thinking to ourselves “what if no one shows up?” We’d secured space, food, t-shirts, stickers, prizes, a photographer, sponsor money, and at the last minute, the cover of the business section of the Star Tribune. Even so, that first Saturday morning at 7am, we were sitting in the eerily quiet space waiting for people to show up and we were still thinking to ourselves “what if no one shows up? what if this is a total bust?” Even after the cover of the business section of a major newspaper!

Turns out nearly everyone showed up (like 48 of the 54 people registered, which if you ever run free events, an 89% attendee rate is unheard of). We even got a visit from the Minneapolis Mayor Betsy Hodges, who stopped by to see what Kristen and I had started and what each team was working on.

That fear on that day, fear of failure, I still feel it in my stomach today. And that fear is SO incredibly overrated. We pushed past it because we knew the benefits outweighed doing nothing.

The last story I want to tell is a quick one about my transition from running a small business for the last 10 years to working at Amazon Web Services. During the nearly ten years running my business, I experimented a lot. I was my own boss, so I could. I experimented with different types and sizes of clients, different lengths of projects, different business domains, different technology, among other things. All that experimentation led me to where I am today. I started learning more about myself and more specifically what I wanted to do. I realized I loved helping people build their software product AND helping them get better with the tech.

A handful of years ago, I started focusing my work on that by working with startups and a few small businesses here in Minnesota. But it was really hard to scale that how I was currently working. There were only so many hours in a day. And as everyone always said, once you go independent, you'll never go back to full-time work. I held onto that for a very long time, maybe even too long. Going to work for someone else after all those years of freedom seemed incredibly scary.

And giving up on a business I had built for almost ten years? Woo! Nothing like feeling like a failure right there. That was a heavy feeling as I considered leaving my business behind.

But at one point, I was reminded that my decision wasn't permanent. I could change my mind at any time. This lowered my risk and gave me space to try a new thing. So here I am today. Trying that new thing.

This experimenting and learning and failing and trying again thing. it goes beyond just our teams at work and the software systems we build and manage. We do this in other parts of our lives too.

Next Up

In the part 2, we'll take a look at how to cultivate a culture where failure can be celebrated.